In my last post, I talked about the power of getting specific about goals for community engagement when partnering with planning agencies. A few times in speaking with planners, it’s been clear that we were talking past each other a bit. Where I, as a museum exhibit developer, can get hyper-hyper-specific about goals for each and every interactive within an exhibit, the planners’ goals are much bigger picture. Which makes sense – the sheer breadth of planning issues, from climate to transportation to health to housing to just about everything else, means they have to think big-picture.

And yet, it’s worth combing through a few of those broad goals – because there’s a lot of meat here for potential museum programs, exhibits, and partnership projects. Here are just a few to get you started.

1. Building Public Awareness of Planning

This is the big first step. Carolina Prieto, formerly of the Massachusetts-based Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) says that in the United States and Canada, community engagement is based “on the idea that planning is--should be--a community activity,” which starts with knowing that it exists at all. (Checkout MAPC’s flikr page to see how they integrate educational displays into their community listening sessions.)

When we embarked on creating the City Science exhibit, our team didn’t intend “building awareness of planning” to be one of the exhibit’s goal – our stated theme was exploring the science hiding in plain sight in cities – but planning themes emerged in visitors’ minds, nonetheless. Throughout the front-end and formative evaluation stages of the exhibit’s development, we found people loved thinking about the past and future design of their communities. And this carried through to the final exhibit.

The summative evaluation1 of the exhibit found that the vast majority of visitors surveyed selected the following as themes for City Science:

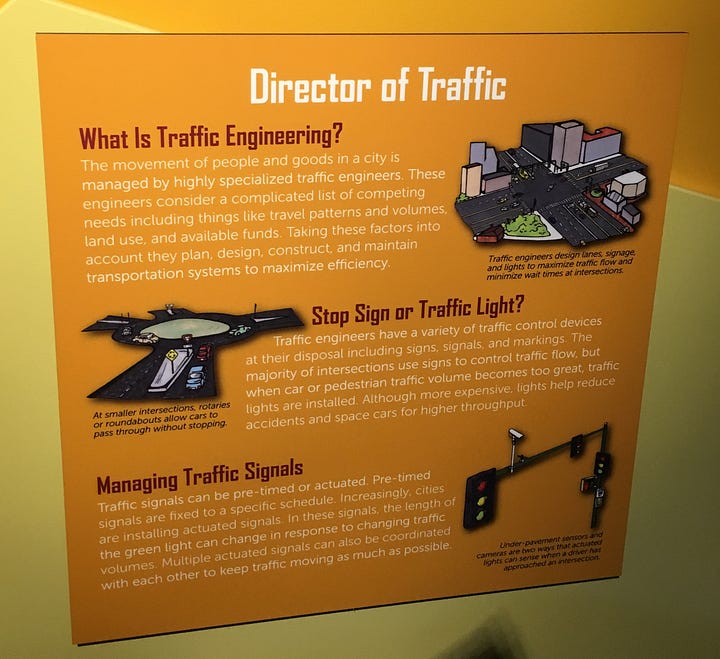

“There’s a lot of science and engineering in cities that you don’t think about.” (picked by 93%)

“There are many factors to consider when designing a neighborhood.” (86%)

“The environment is affected by what people build.” (82%)

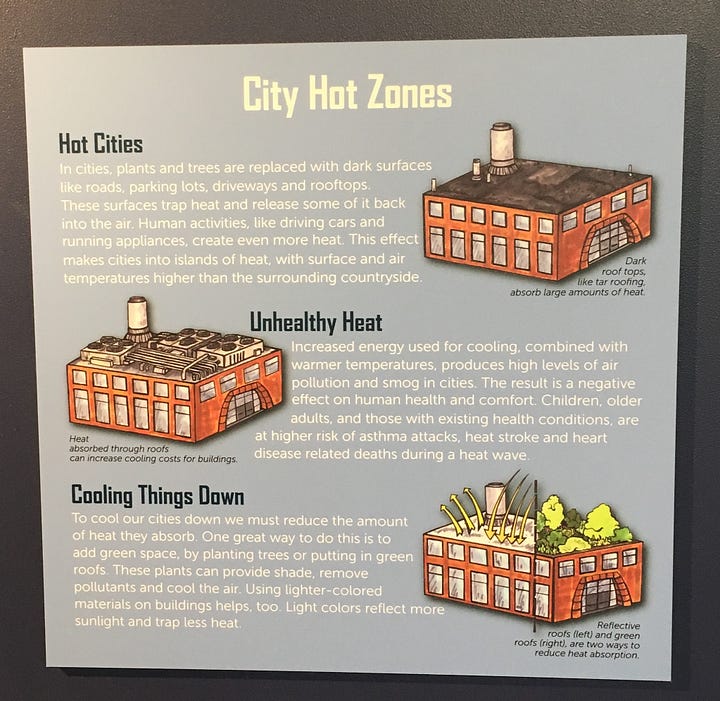

In addition, three-quarters of visitors said that the exhibit made them curious to learn more about topics

like urban heat islands, bridge and building engineering, and traffic lights. And visitor’s answers to open-ended question about exhibit themes included: “How to think about designing your city and making it ecologically friendly … it’s not something you think about every day.” “What goes into planning a city and what makes it work and keeps it clean.” “Understand what things happen in the city; problem-solve how to build a city.”

2. Gathering Broad Public Input into Plans

City of San Francisco planners used the exhibition Middle Ground: Reconsidering ourselves and others, installed by the Exploratorium in a public plaza, “to ask questions like ‘What should our streets be like?’ that we can only ask of people during the course of their everyday lives,” according to former S.F. planner Neil Hrushowy. He also noted that the exhibits engaged thousands of times more people—and a greater diversity of people--than would ever attend a planning board hearing.

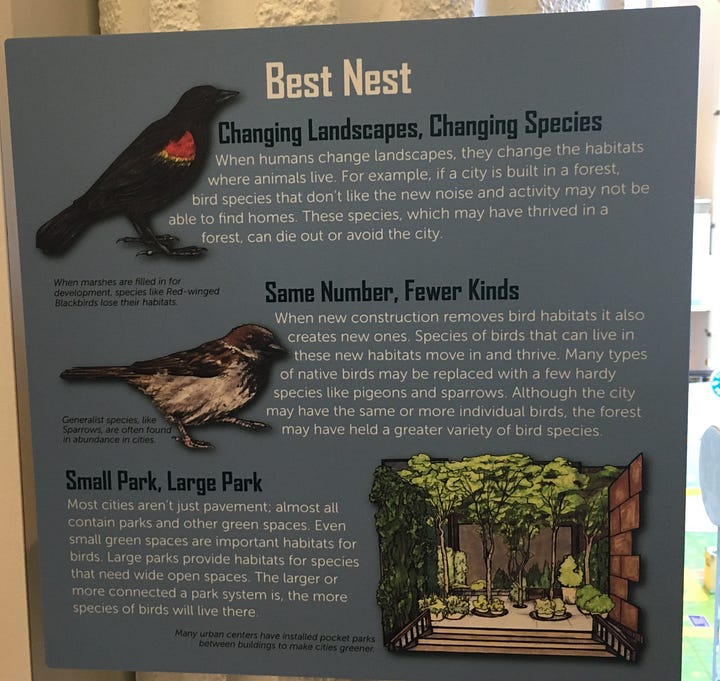

In City Science, our research partner, Robert L Ryan, Chair of University of Massachusetts Amherst’s Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning department, used the “Magnetic Neighborhood” interactive to gather people’s preferences for different types of urban greening.

Imagine if we on the City Science team had also thought to partner with our local city planners. I immediately envision a station where people could have offered feedback to their city officials – newly armed with a better understanding of the inequitable distribution of urban green spaces, of the health impacts of heat islands, and of land use change on biodiversity. Surely this could have been better than sticky dot voting on posters of semi-decipherable policy questions.

3. Building Civic Infrastructure

This really follows from 1 & 2, but it’s important to note, because, as Neil Hrushowy points out, municipal planners are civil servants with “little innate power” relative to elected officials and private developers. Good community engagement builds a “civic infrastructure” that includes the voices of all residents, “not just those who show up to yell at public hearings.” Inclusion is about granting power--to citizens and to planners, he explains. Gaining public support for master plans “grants us [planners] power through good direct democracy” and prevents elected officials from killing progress by saying, ‘I want to go back and study this.’” In fact, community engagement consultant Dave Biggs casts this as gving courage to elected officials in this Planetizen article “Why Bother with Community Engagement?”.

Which hints at another important goal within this goal: people need to know what planning is, what it can do – and what it isn’t and can’t do. Carolina Prieto described this as helping people understand the process and policy “levers” that can affect change. (In their report about developing the MetroCommon2050 plan, MAPC includes descriptions of the ways that public input helped shape the plan.)

The bottom line is that plans are just that – plans. They don’t become actions and infrastructure until they are enforced by policy and code and moved forward with investments. Which means that the civic infrastructure has to be strong enough to shepherd progressive change through the nitty-gritty of zoning and building codes. This feels like a nice job for museums that deal with history, law, or civics. If someone knows of an existing example of this, please send it to me and I’ll share it out!

These three goals are just a taste, but if you’re like me, you’re immediately thinking about a dozen worthy sub-goals and evaluation metrics: Does participants’ increased awareness of planning lead to increased interest in reading their community’s plans? An increase in commitment to participation? Or even, does learning about awful past practices, such as redlining and urban “renewal”, alter participants’ priorities for future plans?

You get the idea – plenty here to get museum geek-y about!

~ Betsy Loring2

The Planning-Curious Museum Person

Sharing stories and ideas for other Planning-Curious Museum People and for Museum-Curious Planning People.

By the way…

If you’re already engaged in a museum-planning collaboration, tell me about it! Interested in expLoring a collaboration with me? Let’s talk! betsy@exploringexhibits.com.

Help me grow the PCMP community - forward this to someone else!

Conducted for us by People, Places, and Design Research.

Betsy Loring is founder of expLoring exhibits & engagement. She has over 20 years’ experience in project management and exhibit development in multidisciplinary, indoor and outdoor museum settings. Her services include exhibit master planning, content and interactive development, and writing, with a focus on hands-on STEM. She also offers staff training in exhibition planning, formative evaluation, and prototyping. Special interests include multi-institutional collaborations, peer-to-peer professional development, and of course – collaboration with municipal planning practitioners.